Behaviors Book

Articles

A quick validation checklist to run before committing to work. Helps teams avoid building solutions to unclear or unimportant problems.

A product manager walks into your office and says, "We need a report that shows daily active users by region, broken down by feature usage, with trend lines for the past 90 days."

You nod. Sounds clear enough. You estimate it, add it to the backlog, and two weeks later you deliver exactly what was asked for.

The product manager looks at it, says "thanks," and then... nothing. It sits unused.

A month later, they're back asking for a different report with slightly different breakdowns.

What happened?

You built the thing. You didn’t solve the need.

A while back I worked with a large manufacturer that needed to modernize a system that managed a key part of their operations. Once completed, the company projected savings of more than $100 million a year.

The plan was to go big. A highly detailed three-year plan.

They assumed that if they were to get a large solution done, they needed to tackle it in big steps.

We suggested small steps.

Here’s what happened.

The problem with "fail fast" is that it too often becomes "move fast." Failure is hidden or spun as success, speed is rewarded, and the learning part gets lost entirely. At its worst, "fail fast" is an excuse to rush into the next thing without pausing to understand what just happened.

What I want to promote instead is Observe Often. The shift in language is intentional—when we say “observe,” we bring focus back to what matters: seeing, measuring, and learning from what we do. And “often” reinforces frequency over haste. It’s not about reckless speed; it’s about small, deliberate moves and frequent feedback loops.

The other day, I was in a Slack discussion with some of the good folks at Test Double. The topic of bug bashes came up, and the conversation was rich. People brought thoughtful perspectives and experiences, and the discussion left me reflecting on what bug bashes say about the systems we work in.

Many teams want to release faster. Some even feel pressured to. They set up CI/CD pipelines, automate deployments, and start talking about daily pushes. But then things go sideways. Bugs slip through. Customers complain. The team’s stress level skyrockets.

The problem with the term best practice is not always the practice itself—it’s the perspective the phrase invites. Best is steeped in finality. It implies that nothing better exists, or ever will. That the thinking is over. And while we may not mean it that way, language shapes thought. When we call something “best,” we stop asking “is it still working?”

These days, it seems like even talking about diversity and inclusion can spark a political debate. But here’s the thing—it doesn’t need to be political. This isn’t about left or right. It’s about people. It’s about teams. It’s about building environments where different perspectives aren’t just welcomed, but seen as essential.

Because they are.

In tech, in product, in leadership—diverse teams consistently outperform homogeneous ones. Not because it feels good, but because it works better. This is a business discussion. A design discussion. A collaboration discussion.

So let’s talk about it.

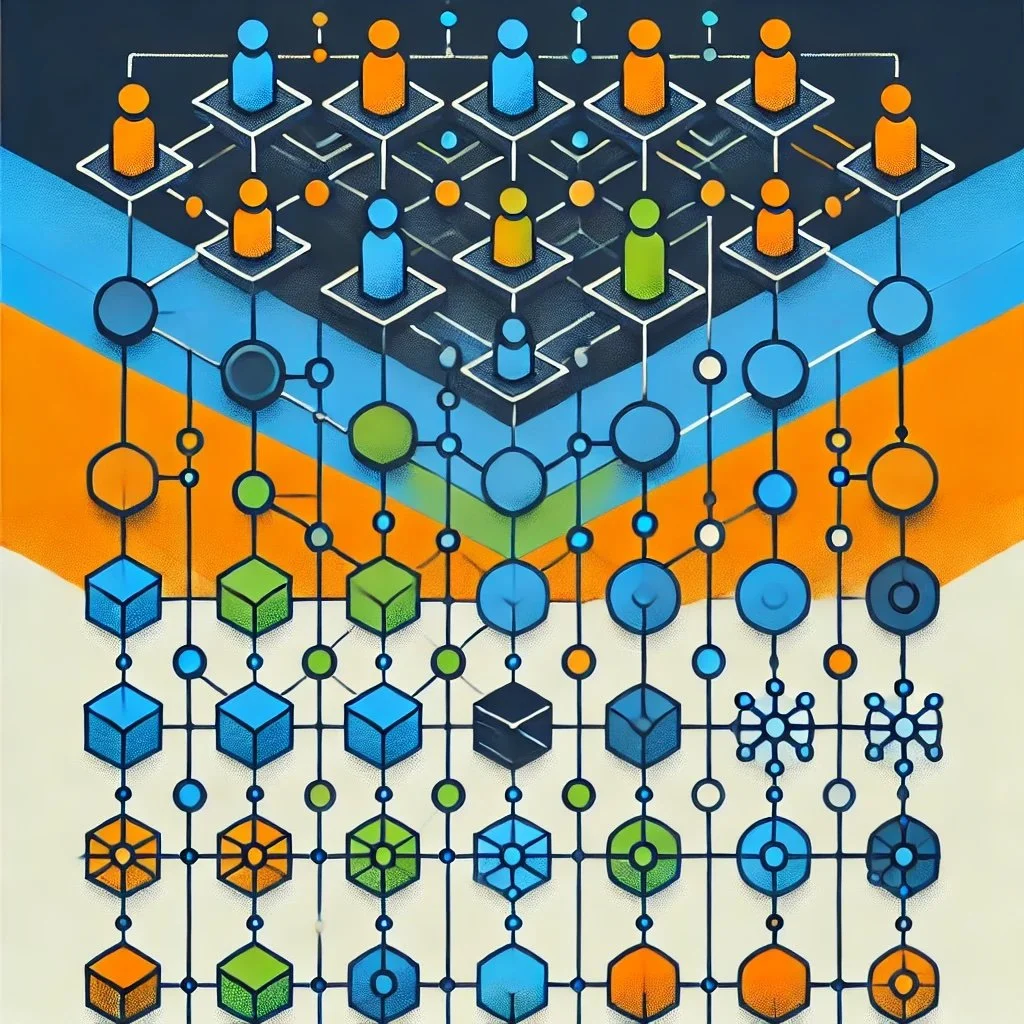

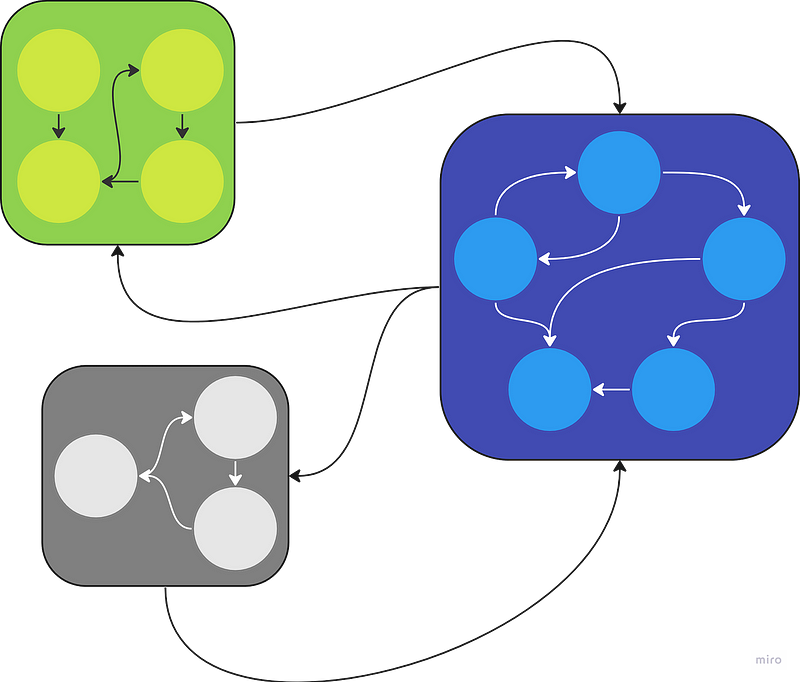

The way your teams are structured shapes the software you build—and vice versa. In this article, we explore the profound connection between team and software composition through the lens of Conway’s Law, uncovering how misalignment leads to chaos and inefficiency, while thoughtful alignment drives collaboration, modularity, and adaptability. Learn why your true architecture isn’t in diagrams but in the code itself, and discover actionable steps to align your teams and software for better outcomes.

When I say I’m joining Test Double as their new VP of Delivery, I’m not just making a career move—I’m making an alignment move. This is a company that already values the things I value. They’ve built a strong culture, a strong team, and a strong set of practices. I’m not joining to overhaul anything. I’m joining to help make something great even better.

When teams hear about small, frequent deployments, they often picture chaos: code breaking, users complaining, and developers scrambling to fix issues. But in reality, small deployments do the opposite. They reduce complexity, amplify feedback, and create a smoother experience for both users and developers.

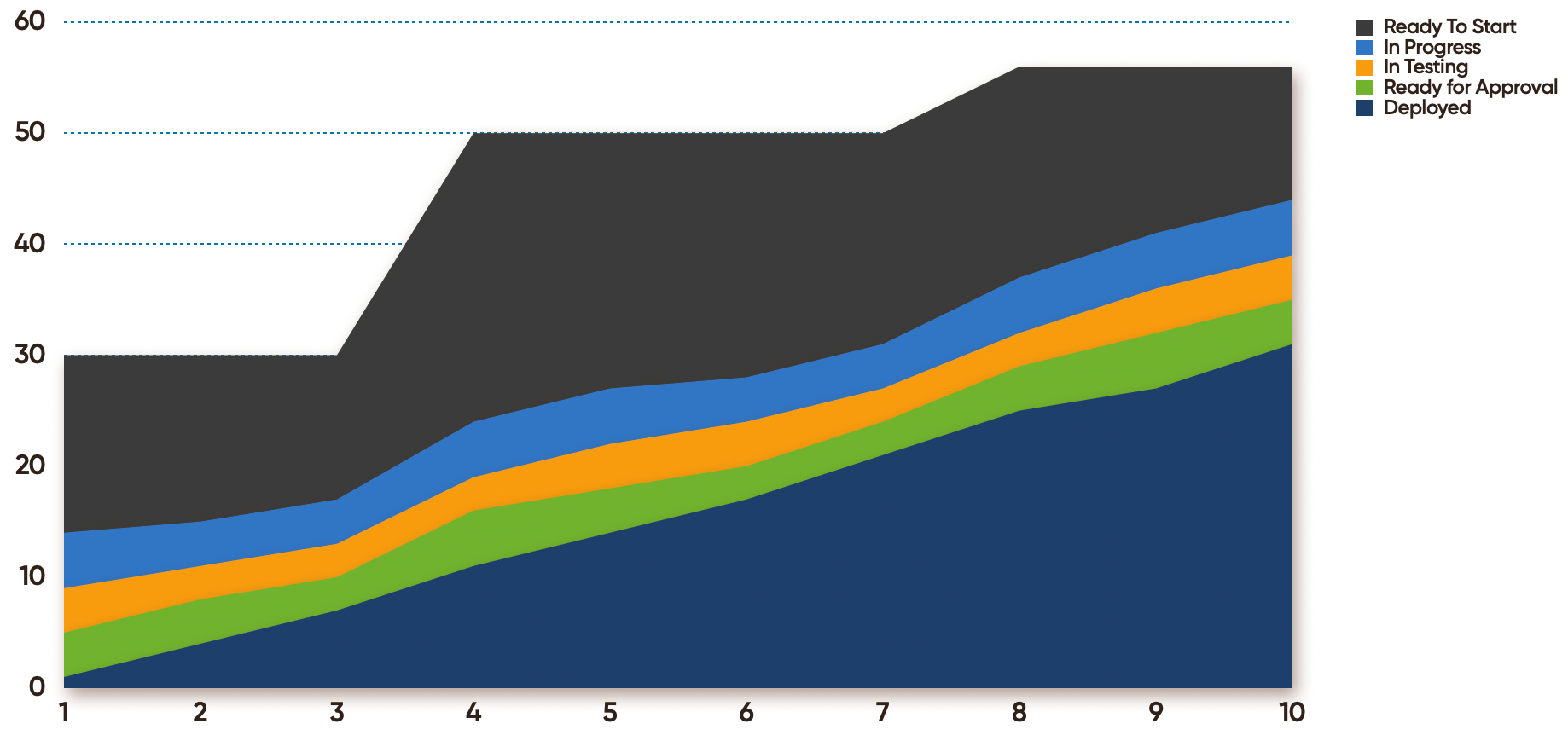

When we talk about making the work visible, there are two key aspects - what is the work and how is the work progressing. In this article, we are going to focus on how the work is progressing. Specifically, we are going to look at Cumulative Flow Diagrams as a means of visualizing work progress.

Whether you’re still figuring out your general product offering or you are enhancing and adding capabilities to a well established product, the ultimate test of whether or not you’ve hit the mark (or are at least trending in the right direction), is how your audience engages with what you’ve created. Yes, you can (and should) do market research before designing and coding up a potential solution to an identified problem, but the only way to know for certain, is to see what happens when your concepts come in contact with your audience.

So you’ve got some problem you’re trying to solve (Know the problem you are solving). You’ve agreed to work together on coming up with a solution. So you call a meeting and ask everyone to bring some ideas.

The objective of the meeting is to select the “best” option among the ideas presented.

In my observation, most folks tend toward an approach I call “Judge and Jettison”.

In this article, I want to go more in depth on Opportunity Solution Trees; what they are, how they are used, how to create one, and how I think about them slightly differently (but only slightly) than folks like Teresa Torres who really introduced them broadly to the Product community in her book “Continuous Discovery Habits”. This book, by the way, is a must have for anyone who works in software product development - not just folks in product-specific roles.

The Experiment Canvas is a simple means of planning, tracking, and responding to your experiments.

The seventh behavior, “Release ridiculously often,” is usually met with nods from half of the crowd and raised eyebrows from the other half. The nodders want to know why it isn’t higher on the list and the eyebrow-raisers want to know the definition of “ridiculously often”.

Composition refers to the way in which something is put together. Composition is a key element in many of the things humans create. Whether it be a musical piece, a painting, a garden, or a building, the way we assemble the core components — the composition of them — has a significant impact on the overall experience.

If you are not familiar with Liberating Structures, I suggest you take a look at them. I use a few of them now and then as circumstances warrant. In future articles, I will discuss some of the others, but today’s installation is dedicated to the Liberating Structure I most often use — 1–2–4-All.

To validate is to confirm something has the quality of being well-grounded or correct. Validate before, during, and after is a reminder that teams should be confirming along the way.

Favor automation over documentation is, to a great extent, about reducing friction - reducing the cognitive load and minutia required to get the work done, allowing you to focus on the value being delivered over the means of delivery.

Gall's Law suggests that for software teams seeking to build efficient, manageable, and scalable solutions, they should start with something simple and then evolve it.

Simple Things

When I say simple, I don’t necessarily mean easy. And I certainly do not mean crude in form or incomplete. Simple indicates something that does not have superfluous parts or multiple responsibilities, is easy to understand, is as independent from the rest of the solution as possible, and meets a need as is.

Simple may not address all use cases, but it does address some use cases.

When I say, “work together”, I mean just that. Do the actual work together.

Every aspect of the product lifecycle is an opportunity for collaboration - Identifying problems to solve, user and market research, design and architecture, formulating experiments, development and testing, deployment, monitoring, maintenance, and gathering user feedback.

A lot of teams have a backlog of some sort and some form of Kanban board — whether it is Jira, Trello, Monday, Asana, MS Project, or a bunch of post-its on a wall. These are all ways of making the work visible. But they aren’t enough.

There are two key aspects to making the work visible; what is the work and how is the work progressing.

“Know the problem you are solving” is about knowing the specific problem and for whom this problem exists. It isn't about knowing what solution a persona lacks but about truly understanding a persona's needs and challenges.

Over the past several years, as I’ve been helping teams and organizations improve their ability to deliver software products that are desirable, viable, and feasible, I have been experimenting with a Behavior Framework that has proven to be rather effective. And I’d like to share it with you in hopes that you find it useful and that you provide me feedback on your experiences with it.

My plan is to write a series of blog posts all related to the behaviors framework. Some of them will be about a specific behavior. Some of them will be about tools or techniques that help teams express one or more of the behaviors. Some of them will be my own experiences. And some will be damn near complete fiction.

My plan is to write a series of blog posts all related to the behaviors framework. Some of them will be about a specific behavior. Some of them will be about tools or techniques that help teams express one or more of the behaviors. Some of them will be my own experiences. And some will be damn near complete fiction.